The most common response we receive when we present Absolute Zero to governmental or incumbent commercial audiences is “Oh, but your forecast of future energy supplies is far too low. You should be more optimistic.”

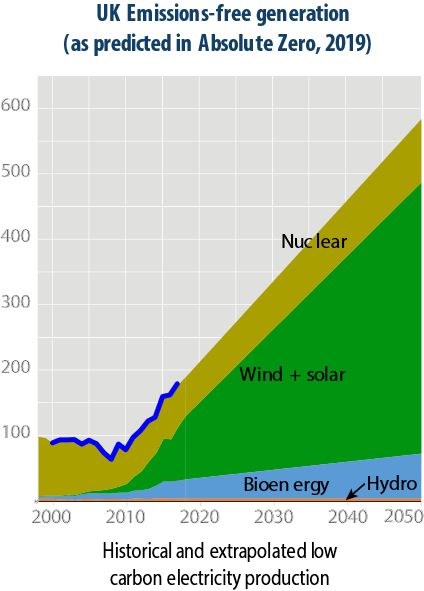

Figure 1, shows the basis of our thinking at the time. The background of this figure is figure 1-1 in the Absolute Zero report, and here we’ve overlaid on it the government’s data on electricity generation. This data, which is available in the excellent Digest of UK Energy Statistics (table 5.6), takes a while to collect and validate, so when we wrote the report in 2019, we could draw on real data up to 2017 – which is the blue line in figure 1.

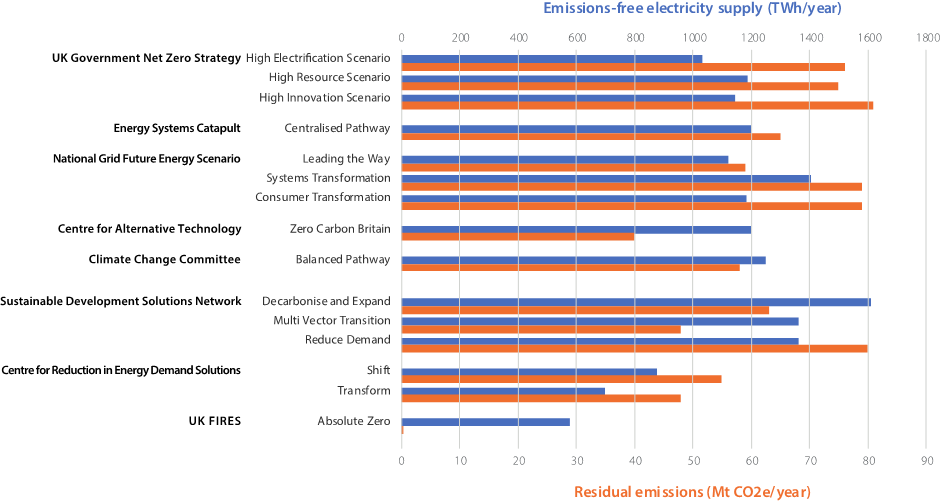

Figure 2 below, certainly seems to confirm that we are less optimistic than everyone else[1]. Compared to 15 other scenarios used to inform government climate policy, our forecast of the emissions-free electricity supply is by far the lowest. Figure 2 also demonstrates that all of these other scenarios depend on negative emissions technologies such as carbon capture and storage to deal with between 40 and 80 MtCO2e per year of “residual emissions.” In Absolute Zero we reflected the reality that to date no such technologies were operating in the UK, and therefore forecast that by 2050 we should continue to anticipate that they would not exist. So far, our prediction on that front has been absolutely correct, although – as always – there are lots of people in the oil and gas industries talking enthusiastically about projects that might happen.

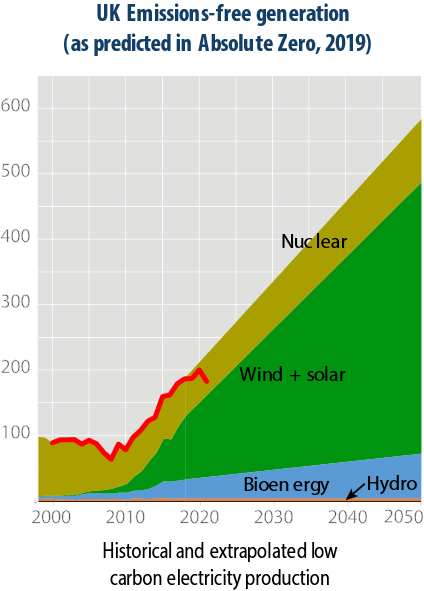

Of course we don’t yet know how accurate our forecast of emissions-free electricity generation will be in 2050, but we can at least examine how well our forecast has stood up over the four years since we published it. Figure 3 is an update of figure 1, with the latest data on the UK’s electricity generation, which has now been published up to 2021. The figure clearly shows a dip in generation during 2021, due to the Covid lockdown. However, even ignoring this dip, there is no hint that our forecast was unduly conservative. In contrast, our prediction turns out to have been higher than what actually transpired. In Figure 2, we appeared to be giving the most pessimistic prediction about the future, but actually even we were more optimistic than we should have been.

Energy infrastructure is not a commodity product, like a smartphone. You can’t buy new nuclear power stations, or carbon-capture and storage facilities off the shelf. They are mega-projects. Before construction begins, a long and complex series of societal discussions has to play out, about public funding contrasted with other important priorities, about land-rights, local communities, safety, public perception, legal and environmental compliance, and the complicated processes of commercial contracting. Once construction begins, it almost always takes longer than predicted – because the contracts are often awarded to the most optimistic sounding contractors, who claim early delivery dates, but then have to push them back as “unexpected” features of the project delay their intended timelines.

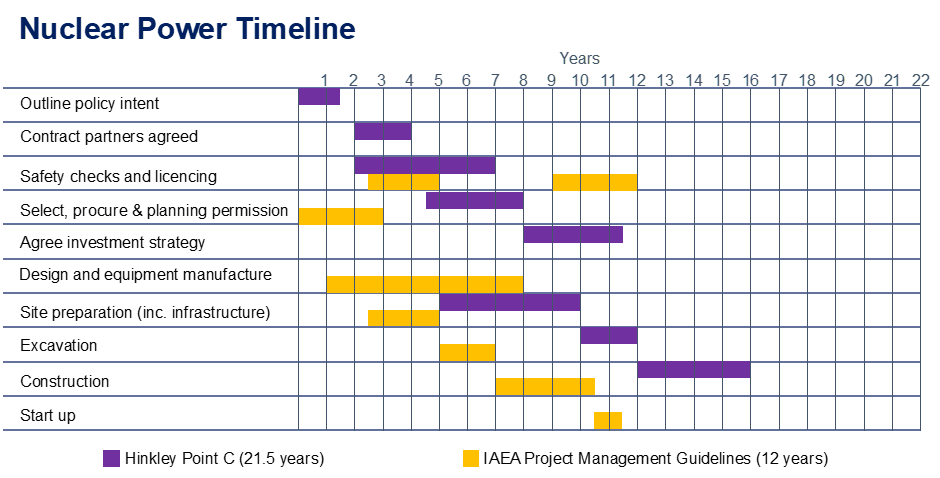

Figure 4 shows how this story is playing out for the new nuclear power station at Hinckley Point C. The yellow bars show the International Atomic Energy Authority’s predictions of the timeline to introduce a new nuclear power station. The purple bars show what has happened to date – and don’t forget that when the latest delay was announced in 2022, the project owners also predicted that they would be announcing further delays later…

Figure 4 shows how this story is playing out for the new nuclear power station at Hinckley Point C. The yellow bars show the International Atomic Energy Authority’s predictions of the timeline to introduce a new nuclear power station. The purple bars show what has happened to date – and don’t forget that when the latest delay was announced in 2022, the project owners also predicted that they would be announcing further delays later…

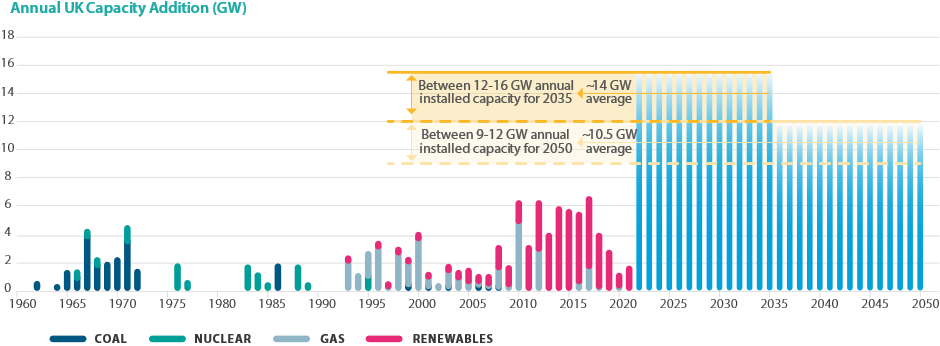

Yet the message isn’t getting through. Atkins in their excellent “Engineering Net Zero” reports have analysed the build-rates required to deliver the energy infrastructure predicted by the Climate Change Committee, leading to the graph in figure 5. Notice that the required build rate leapt up in 2022, to an unprecedented level with no ramp-up.

Almost unbelievably, when this report was launched, the audience response was to smile and shrug, and say “well we’ll just have to go a bit faster then, won’t we? We just need to be more optimistic.”

But surely the correct interpretation of figure 5 is that it isn’t going to happen. There is no possibility of this level of energy infrastructure being built by 2035, and if anything approaching this rate of construction is to happen beyond then, the public financing commitment needs to be made right now, before the next election.

We haven’t heard it mentioned.

When we hear people tell us that we “should just be more optimistic” we think what they’re really saying is “we don’t want to think about a future in which we don’t have all the energy we want.” But the whole excitement of the UK FIRES programme has been to recognise that that such a shortfall is (close to a certain) reality, and as a result a whole different range of innovations in technology, business, systems, governance and lifestyle are going to emerge as the enablers of real zero emissions living. By articulating and promoting those opportunities, we are aiming to open up a much more credible pathway to delivering zero emissions in reality. These are achievable goals, and it’s a pathway along which we can walk to a zero-emissions future – while living really well.

Julian Allwood, March 2023

[1] This figure is adapted from figure 4-3 in Sam Stephenson’s UK FIRES research paper “Technology to the rescue? Techno-scientific practices in the UK Net Zero Strategy and their role in locking in high energy decarbonisation pathways” which is currently under review.